After spending years of their childhood finding ice-age fossils, the world famous "Boy Paleontologists" found themselves in the Children's Natural History Museum in Fremont on Saturday — back among the many artifacts they dug up years ago.

|

|

|

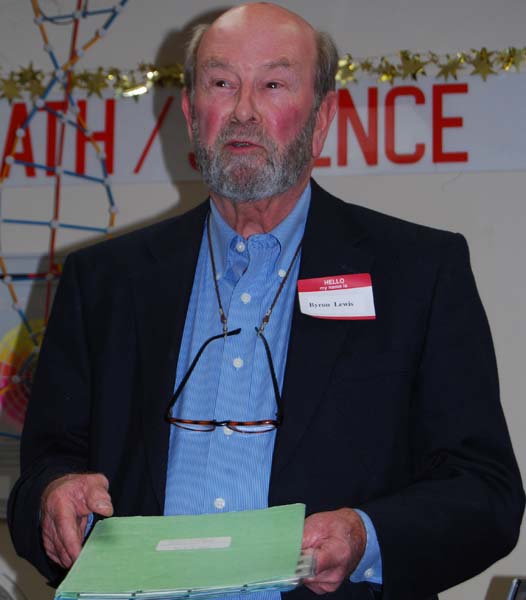

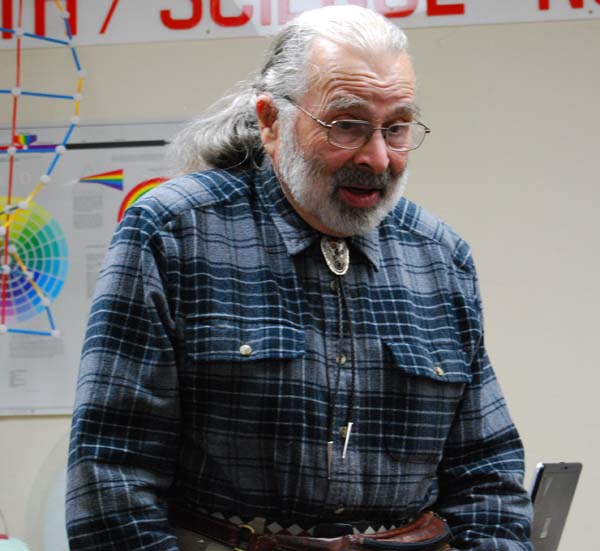

| Phil Gordon | William Charles | Byron Lewis |

Five of the 16 members of the 1940s group were on hand for the "Preserving Our History" fundraiser for Fremont's Math Science Nucleus, which oversees the natural history museum. Of the five, four were part of the original Hayward Rockhounds, as the group was known before gaining the nation's attention in Life magazine.

|

|

| Bill Seaver | Jay Broadwell |

Attendees were able to meet the Boy Paleontologists, hear their stories and have them autograph photos that ran in Life. "This is exciting for us," said William Gordon Charles, 72, who hadn't seen some of his former diggers in well over 40 years.

The now-retired men, some well into their 70s and even 80s, were responsible for uncovering one of the largest preserved fossil sites in North America in the early 1940s. Most of the fossils were from the Irvingtonian Age, named after the Irvington district in which the fossils were found. Their finds led to national media coverage, including a story in the December 1945 issue of Life that gave the group its new name.

"We started out as the 'Rockhounds' until the Life magazine article came out," said Bill Seaver, 78, who now lives in Southern California.

|

|

|

|

Evelyn Cormier, President of Ohlone Audubon (left) is given a round of applause from Bob Wieckowski (Fremont Council Member, and Pat Gordon (right) |

Joyce Blueford, Board President of Math Science Nucleus is happy to receive $1500 check from Ohlone Audubon and $2500 from Bob Wieckowski |

It all began with Charles' father Wesley Gordon, who worked for the Hayward Recreation Department. He was looking for activities for kids who were finding their way into trouble during a time when the men were at war and the women were busy working.

Gordon began taking youths on Saturday hikes, during which they would find old Indian artifacts along Hayward Creek. "One day "... we found a tooth of a mammoth in the Hayward Creek," Charles said. "That was the first time we found anything in the fossil sort." Eventually, the group would find itself out at Bell Quarry, in cooperation with University of California, Berkeley, scouring the gravel pits for fossils.

"As soon as we got out (of the car) we found fossils on the ground," Charles said of the first trip to the quarry. Many of the kids who took that first quarry trip didn't give up the fossil hunt until it was time to go to college. Eventually, 16 boys in two cars would be making the trip, until Interstate 680 was built on top of the quarry.

Jay Broadwell, who was 13 at the time, was among the first youths to venture out with Gordon. Looking back on that time, Broadwell — now a 79-year-old Lafayette resident — attributes much of his later success to digging up fossils.

"I know for me it lead into two scientific careers," he said. "All my life has had me looking at things "... It just changed you. It gave me a quest for knowledge. I am severely dyslexic so I did poorly in normal school, but I wouldn't have had the drive I got from the 'Boy Paleontologists.' "

"We did something exciting," Charles added. "It was like digging for gold. We yelled and screamed at every fossil we found. We were wartime children digging for fossils."

In all, the boys would find well over 20,000 fossils at the site. Most of the finds remain housed at UC Berkeley, with another 1,000 at the museum and 1,000 more at Ohlone College.

Museum officials expected a few hundred people to greet the Boys during the Saturday fundraiser, as well as view actual the fossils of mammoths, sabertooth cats, mastodons and sloths they dug up decades ago. On Saturday night the museum was to host a reception in honor of the Boy Paleontologists.